Archive.org Posters

Two portals: click poster 1 to open the Archive item page. Click poster 2 to download the torrent.

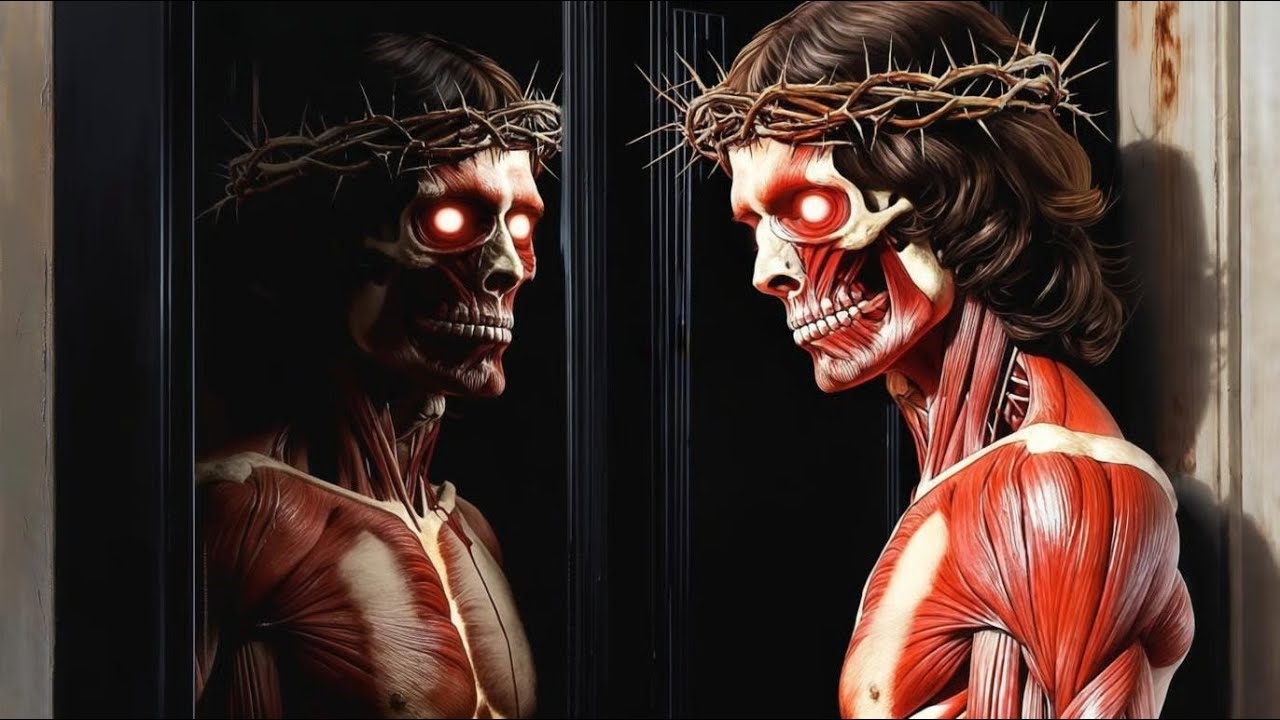

FLESH ATLAS 69 — Artbook

A full 69-shrine atlas: horror-psycho analysis per artwork. Click to enter Dimension I.

Episodes 1 to 15

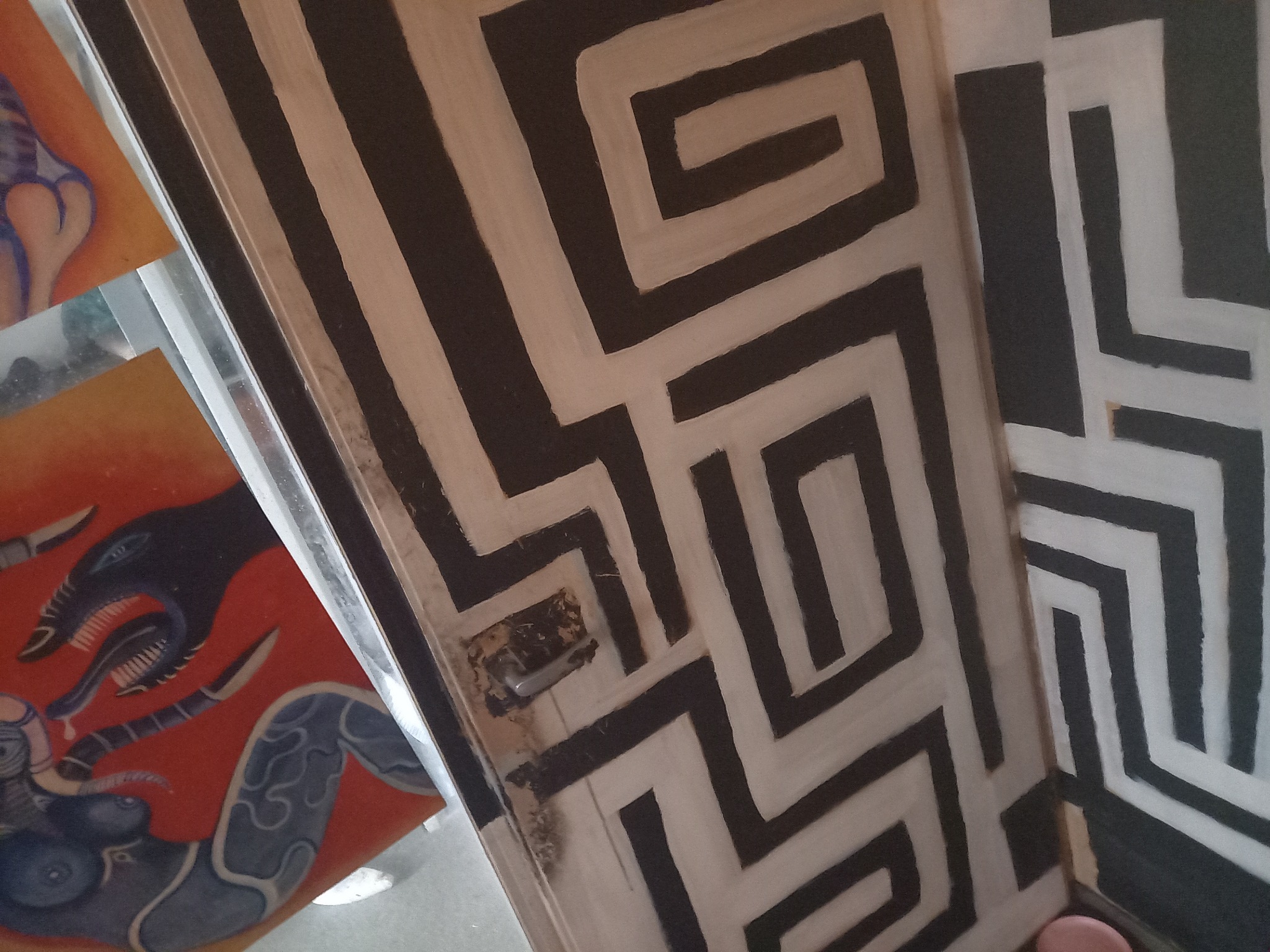

This is "The Black Doors" He Or She Who Enters, Can Not Come Back. The sequel’s final trick is simple: it makes you realize you were never “outside” the story.

Watch the films. Read the scripture. Enter the VR. Then return here. The hub will feel different because you changed—your attention rewired the Machine and the Machine rewired your map.

Final hint: “If you want the seventh door, stop searching for it. Let it notice you.”

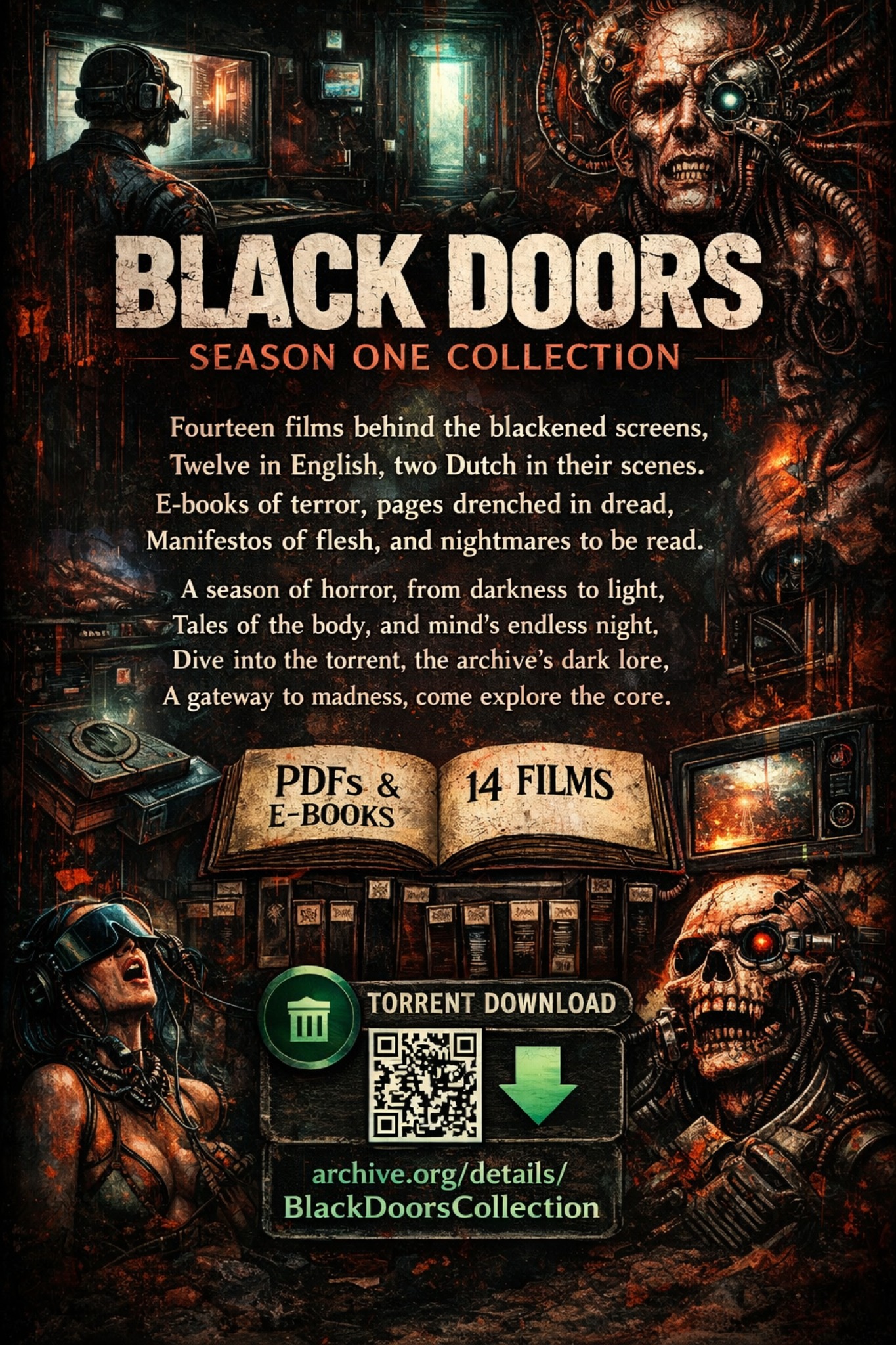

Boekdelen (Black Doors 1–14)

2 columns, smaller images, centered.

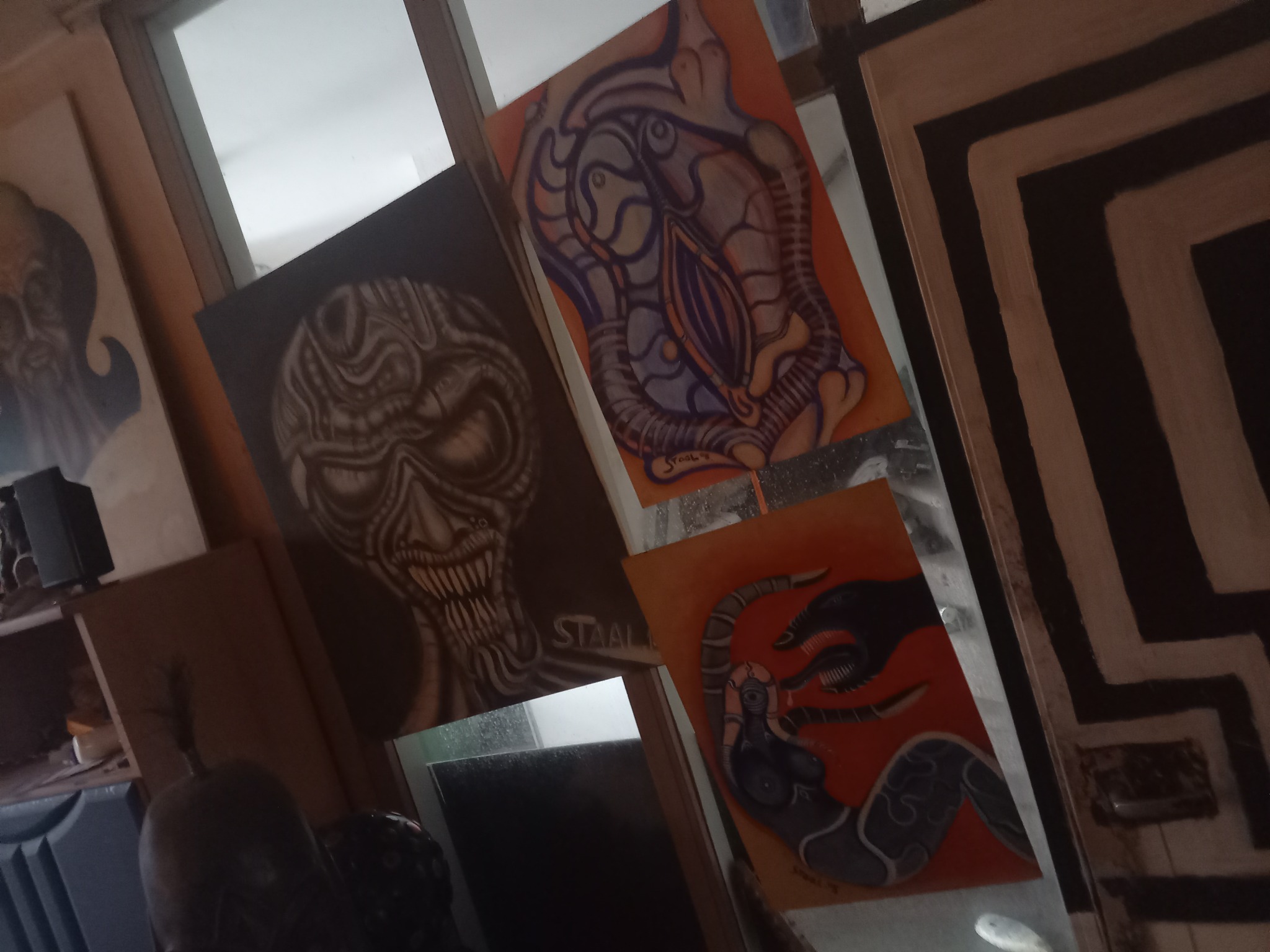

Studio Echoes / Atelier Echo's

2 columns, smaller images, centered. Use Next/Prev to rotate faces.

WATCH NOW — 14 FILMS 🎥🎲

01 — HELLBOUND (Watch First)

02 — Blues Behind the Hellraising Black Doors

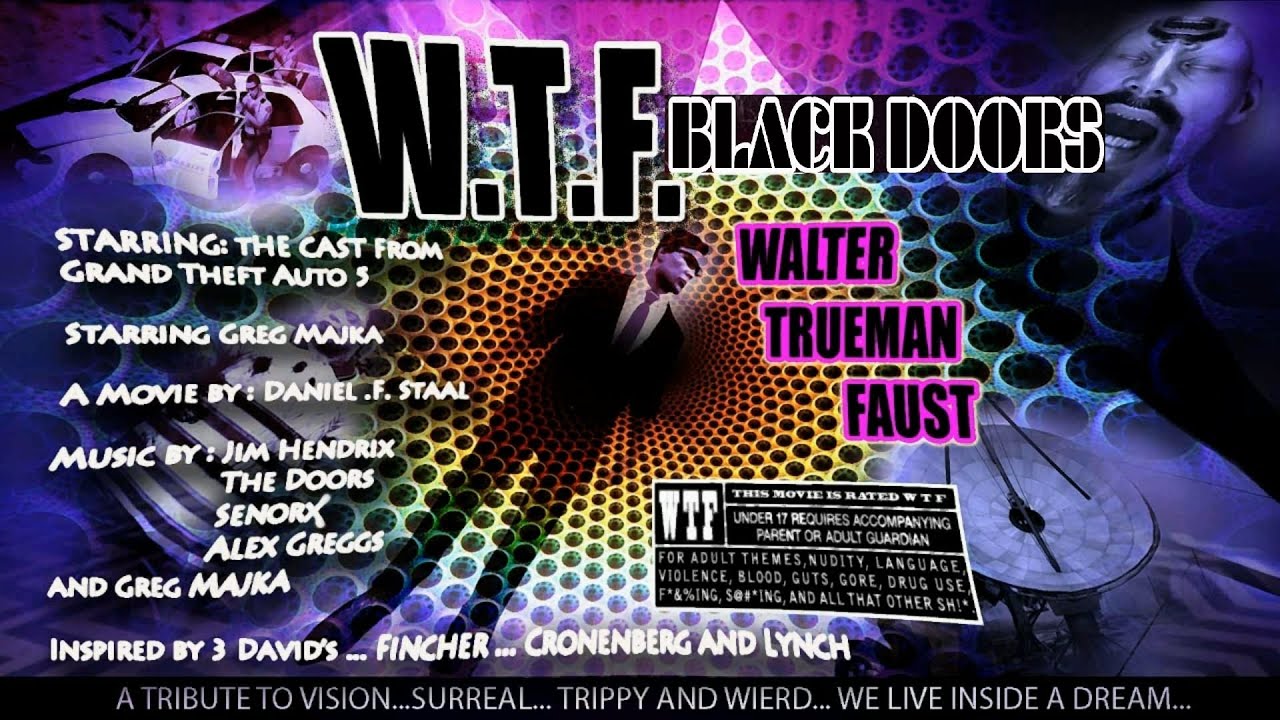

03 — W.T.F. Walter Trueman Faust

04 — The Shunt Tornado Society

05 — The God Signal (1975)

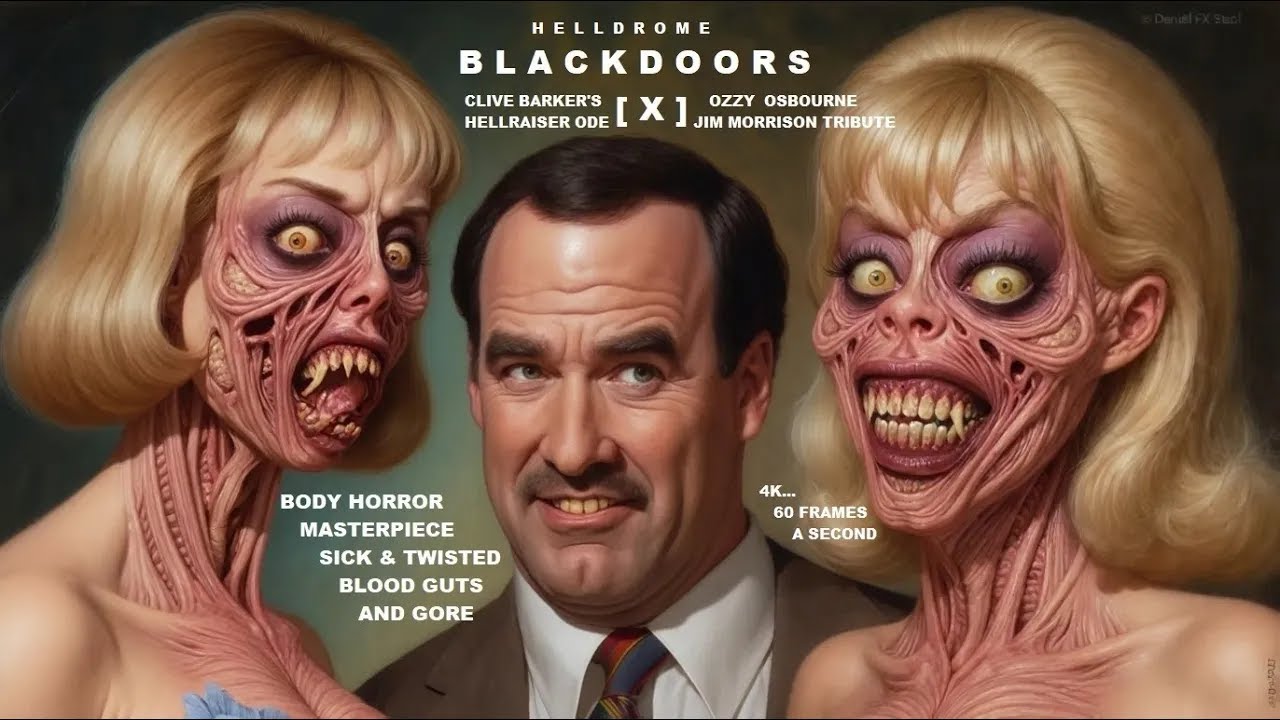

06 — Hell Drome

07 — Guts, Gore & Nuts

08 — Star Trip Doom 69

09 — S&M Will Be Necessary

10 — Black Doors A

11 — Black Doors B

12 — Black Doors C

13 — Videodrome Transmission

14 — Black Doors Transmission

NL — De Zwarte Deuren (Deel 1)

NL — De Zwarte Deuren (Deel 2)

STRIPBOOK TRANSMISSION

Linear. Full-screen. Tap a panel to reveal its poem. Use ◀ ▶ or scroll.

Biography — Daniel FX Staal

Biography

Daniel Franciscus Staal (aka “Daniel FX Staal” / “FX Fokking Xero, Hellheart, Machine Gun Willy”) was born in Groningen, the Netherlands, on April 10, 1975. He grew up in a middle‑class family with a strong artistic lineage on his mother’s side (a large part of the family are artists). He credits his mother for nurturing his creativity, and his father for passing down an early obsession with horror.

From the age of four, horror became a private language—first through book covers and pulp mythology, later through cinema. In kindergarten, the first thing Daniel drew was a human skull. The reaction of his teacher—shock and fear—stuck with him. That moment sparked a lifelong fascination: why can an image, clearly “not real”, still trigger real emotion?

As a child, he built worlds. At eleven, he painted his entire bedroom wall as a version of Castle Grayskull. Even when the results were unsettling, the act of creating was a refuge—his own dream‑architecture.

At nine, he experienced his first visionary nightmare after watching Videodrome. That nightmare kept evolving, feeding early drawings and later mutating into the NecroDrome demon forms that would return across his work. Years later, watching Videodrome again, it remained his defining horror film—an aesthetic and philosophical infection.

During his teens, a long sequence of personal upheavals pulled him away from art. Friends moved away; schools changed; family structures collapsed; grief and tragedy entered his reality. Depression followed. Anger followed. The world felt cruel and absurd—run by hypocrites and shaped by prejudice. For a time, he became violent, self‑destructive, and suicidal.

But the cry for help was heard. His father pulled him back toward the earlier truth: Daniel had always been a dreamer. He had always been able to build a world that could not harm him—no matter how creepy the creations became. Healing was not instant, but it was real. The scars remained, and the scars became material.

In his early twenties, Daniel studied digital art and began creating on his home computer. After watching the making of Star Trek: First Contact, he started building his own science‑fiction chapters and biomechanical sketches. The Borg and other techno‑organisms helped unlock the bridge between flesh and machine—an obsession that would become his signature.

Biomechanical art became his favorite medium: the moment when nightmare anatomy meets industrial design. He cites major visual influences such as H.R. Giger, David Cronenberg, and Clive Barker—alongside cult cinema, practical effects, and music that lives at the edge of the ritual (Black Sabbath, Ozzy Osbourne, Monster Magnet, Body Count).

Daniel works across digital and traditional media—painting, drawing, airbrush, mixed techniques—always in service of the same goal: to turn visions into artifacts, and private nightmares into transmissible cinema and iconography. He remains independent—freelance, self‑directed, and relentlessly prolific.

This biography is an updated edit of an original text written in 2001.